Paris violin maker Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume (1798-1875) achieved tremendous recognition during his lifetime for his beautiful and consistent workmanship and the responsiveness of his instruments. His workshop employed many of finest best violin and bow makers of the day. They produced instruments inspired by models from Stradivari, Guarneri del Gesu, Nicolo Amati, and Maggini. Some of these instruments were “bench copies” with skillfully antiqued varnish made as meticulously detailed replicas of especially notable instruments.

Capitalizing on his popularity, Vuillaume introduced the St. Cecile des Thernes line of violins to serve a broader audience of musicians. These instruments, produced from about 1844 until 1856, bear the image of St. Cecilia, the patroness of musicians, on the back of the violin. The banner below the image reads “St. Cecile des Thernes” (Thernes was the name of the town where his country house was located outside of Paris). The violins were constructed in the Mirecourt workshop of his brother Nicholas Vuillaume, and sent “in the white” to be finished and varnished in Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume’s Paris workshop, thus allowing Jean-Baptiste to maintain final control of the work and quality of his more affordable line of violins. A third and less expensive line of violins called the Stentor was also produced in the Nicholas Vuillaume workshop for sale in Paris, and these violins carry the “Stentor” moniker in a raised banner at the back of the pegbox.

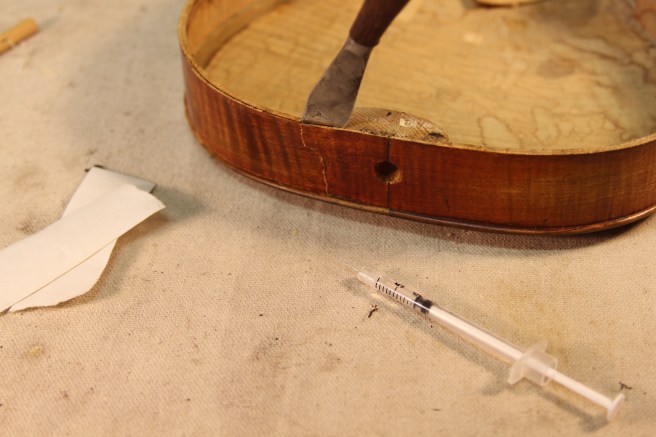

The Vuillaume St. Cecile we have for sale is a Stradivari model dated 1852. It has an attractive one-piece maple back and a body length of 358mm, a typical size for a Vuillaume Stradivari model. It is in particularly fine original condition, retaining its original neck, with a very clear, strong, and robust sound, and is suitable for any level of player.

In 2008 the shop moved from its previous nineteenth century building to the current premises at 507 South Broad Street, the area known as the “Avenue of the Arts.” This building was designed by architect George Pearson and showcases the Aesthetic style then in vogue in London and the East Coast of the United States. Construction began in 1882 and the building was likely finished in 1886, which was when the wallpaper hangers signed one of the walls they were finishing with their names, dates, and their home addresses. The building was commissioned by James Dundas Lippincott and Alice Lippincott as an extension to their home next door at 509 South Broad Street. Telltale evidence of doorways in the walls showed that the two buildings were originally connected. However, they may have been separated from one another as early as 1894, and certainly by 1906.

In 2008 the shop moved from its previous nineteenth century building to the current premises at 507 South Broad Street, the area known as the “Avenue of the Arts.” This building was designed by architect George Pearson and showcases the Aesthetic style then in vogue in London and the East Coast of the United States. Construction began in 1882 and the building was likely finished in 1886, which was when the wallpaper hangers signed one of the walls they were finishing with their names, dates, and their home addresses. The building was commissioned by James Dundas Lippincott and Alice Lippincott as an extension to their home next door at 509 South Broad Street. Telltale evidence of doorways in the walls showed that the two buildings were originally connected. However, they may have been separated from one another as early as 1894, and certainly by 1906.

Italianate home later was acquired by Princeton University in 1878 and is now known as Prospect House. James was born in 1840 in Philadelphia. He graduated from Princeton University in 1861 with a Bachelor of Arts. James Dundas Lippincott and Alice Potter were married in 1867. James and Alice were both from wealthy families. The Dundas family had substantial holdings in coal lands in Pennsylvania. Even after their marriage, Alice received an annuity from her father’s estate. While the couple could have continued to live in the

Italianate home later was acquired by Princeton University in 1878 and is now known as Prospect House. James was born in 1840 in Philadelphia. He graduated from Princeton University in 1861 with a Bachelor of Arts. James Dundas Lippincott and Alice Potter were married in 1867. James and Alice were both from wealthy families. The Dundas family had substantial holdings in coal lands in Pennsylvania. Even after their marriage, Alice received an annuity from her father’s estate. While the couple could have continued to live in the